Russian elections are a sheer pleasure to analyse for three reasons: they are rigged but detailed data on outcomes is available. This winter the country witnessed a great natural experiment: street politics revived after December, 4 Parliamentary elections, with thousands of used-to-be passive voters rallying on the streets. Now we are in a rare position to compare the pre-protest voter with his rioting successor.

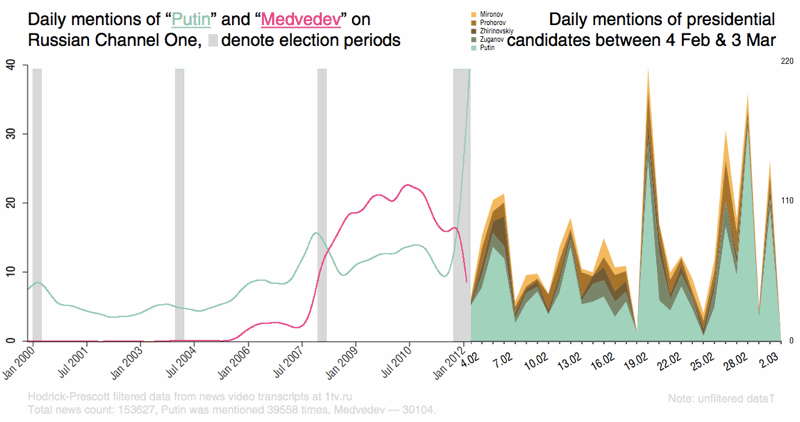

The second natural experiment spawns from the duality of Russia: in the last 20 years the richest Russians doubled their wealth whereas the poorest became 1.5 times as poor. The poor are considered a political platform of a paternalistic state, their world view is shaped by government-owned media:

Propaganda carpet bombing on TV was at all-time high during 2012 elections. Capture of terrorists preparing the assassination of Mr. Putin was widely televised, prompting allegations by opposition that it was staged. Nevertheless, the viewership of Putin was way above other presidential candidates, infringing on their right to be elected.

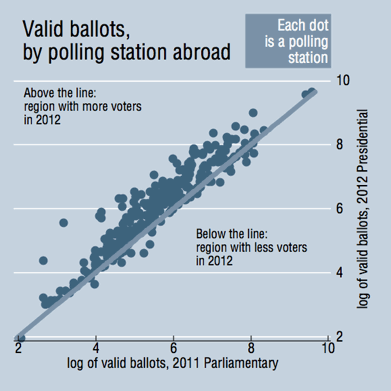

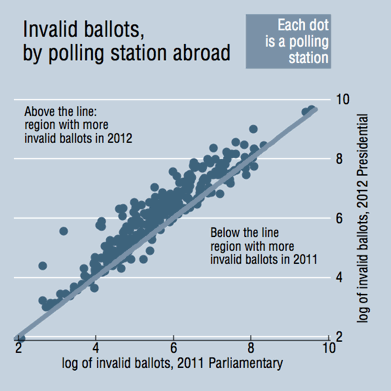

Many have been asking the question why the poor are pro-Putin. However, nobody has ever tried to make sense of another isolated group, which is somewhat antagonised by the state: the Russians abroad. They represent a minuscule 1.43% of voters, but have high political consciousness. It seems that expats did ride the wave of citizen activism and voted more actively during 2012 Presidential elections, compared to 2011 Parliamentary:

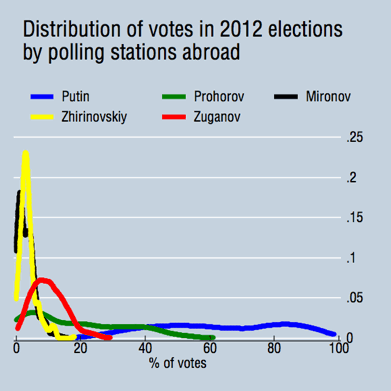

Apart from political responsiveness of the Russians abroad, they also share markedly diverse voting preferences:

It seems that all candidates, except the leading one (blue line, Putin) and a new contender (green line, Prokhorov), have core groups of supporters which do not intersect. Data are drawn from 374 electoral commissions located in 145 countries. This permits us to take advantage of a three-fold natural experiment: (i) the Russians abroad are not covered by state TV propaganda, (ii) they may project the aspirations they acquired outside their country of origin through the ballot box, (iii) they are different. The daunting challenge to reconstruct their voting patterns warrants a quantitative exploration.

Hotchpotch voters

Putin’s mean result (63.08%) by country is lower than the gross one, that is calculated summing all voters, regardless of their country (73.24%). However, this is not the case for other candidates:

| Candidate | mean | gross |

| Putin | 63.08% | 73.24% |

| Prokhorov | 18.68% | 13.56% |

| Zuganov | 10.06% | 7.19% |

| Zhirinovskiy | 3.66% | 2.72% |

| Mironov | 3.28% | 1.96% |

It translates that voting preferences of the Russians abroad were not uniform between countries: states with more voters were pro-Putin.

62 states had more than one polling station, meaning that one can calculate standard deviation of votes for candidates within countries, weighted by valid ballots at polling stations. In other words, we have a metric of how polarised support of a certain candidate was in a given country, which is adjusted by the size of this support. As expected, Putin has the most polarised support, with Prohorov being the second:

Common sense and regressions show that polarisation of voters was not driven by country factors (economic, represented by Human Development Index, or political, represented by polity score). One of the observable factors of polarisation is enclave voting. Having identified 42 enclaves with polling stations inside (military/FSB bases abroad, settlements of engineers (e.g. in Iran), etc.), I see that they vote some 7% more favourably towards Putin than an average polling station abroad.

The shady candidate

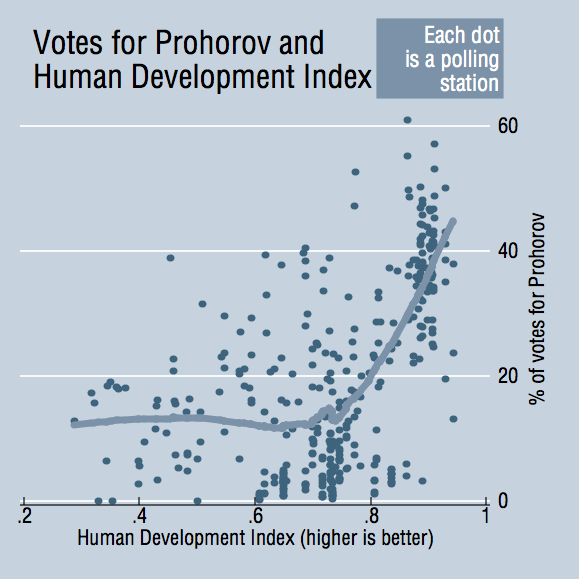

The biggest intrigue of the campaign was, undoubtedly, Mr Prokhorov. A billionaire newcomer to politics presented an eclectic programme with endorsements from popular actors, singers and activists. A hard-working man, with support among rich Russians:

He claimed to be independent but some believed that he was instituted by Kremlin to split the vote of reform-minded Russians. And data proves that he was a success in that sense, at least abroad. We can compare voting patterns at the same 299 polling stations for parliamentary and presidential elections.Which party gave which candidate a boost? To rephrase, a 1% increase in support of a certain party on parliamentary elections gave each candidate an advantage or disadvantage. Below I show them in numerical form (if statistically significant), or just with negative or positive sign (if not significant):

| A 1% increase in support of the ... party↓ gives the ... candidate→ ... more votes↘ |

Putin | Zuganov | Prohorov | Zhirinovskiy | Mironov |

| United Russia | 0.86% | - | - | - | - |

| Communist Party | + | + | + | - | - |

| Liberal-Democratic Party (not really) |

+ | - | + | - | - |

| Just Russia | + | - | + | - | + |

| Just Cause | - | - | 1.59% | - | - |

| Yabloko | - | - | 0.84% | - | - |

| Patriots of Russia (too small, can be ignored) |

- | - | 0.84% | - | - |

The most plausible conclusion we can make from this table is that Prokhorov indeed took the votes of Just Cause and Yabloko, the “democratic” parties. On a side note, it’s impossible to discern voting preferences for people supporting communist Zuganov’s party during Duma elections. It’s means that he was truly the “none of the above” candidate. The alternative strategy of “none of the above” vote was to spoil a ballot. Some opinion leaders of opposition called for such action. Did people listen to them?

Yes, the voters listened to them, but they comprised a mere 12 people per station, or 0.39% of voters abroad.

With the data at hand it is possible to see that there’s a feedback between expatriate community and their homeland. Russian nationals abroad demand a liberal candidate but, ironically, are forced to vote for a communist candidate to register their protest.