Some 236,000 Russians voted abroad on Dec, 4 parliamentary elections. Though this figure accounts for a negligible 0.4% of voters, their support of the ruling party is astonishing: the party of power won with a substantial margin on most of foreign polling stations during 2007 general elections; in 2008 president Putin’s successor was supported by 84.6% of voters abroad (but 70.3% inland). Dec 2011 elections was no exception: international result for the United Russia, the ruling party, was 59.4%, 10pp. ahead of overall outcome. Yet the winner in US, UK, Germany, Switzerland, Netherlands was a democratic party Yabloko which didn’t even pass a 7% threshold at home. People in London queued for two hours by the embassy to vote against (86%) the ruling party, same were the sentiments in other Western European countries. Why then such counterintuitive result? Two explanations should be considered: heterogeneous voters and fraud.

Country-specific basket of political attitudes

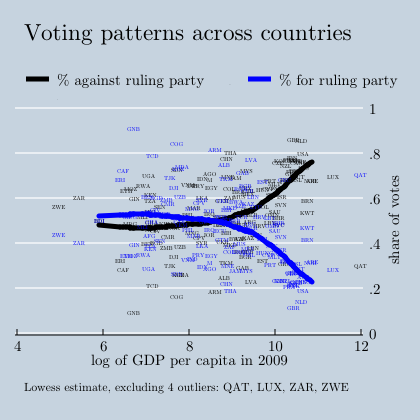

It is impossible to sketch a model voter abroad, regardless of country of origin or residence; every speculation about his/her preferences will be at odds with reality. We are agnostic even about their count. But with the only data at hand being country-level election results coming from 376 polling stations (from Afghanistan to Zimbabwe), it is still possible to capture varying political attitudes. The first thing to tie up is wealth and voting intentions:

With every country’s voting result for Dec, 4 elections contrasted with its GDP per capita, it is evident that from a certain level of host country GDP (~$9,000 per capita) opposition sentiments among Russians there start to grow, hence the lines cross. This is anything but a novel result: political science mainstream view suggests that wealth bring demand for democracy and change. But what kind of change? We are able to decompose this demand:

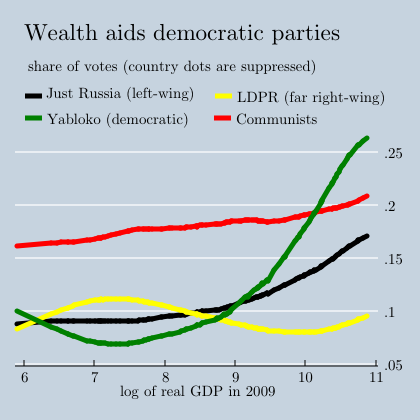

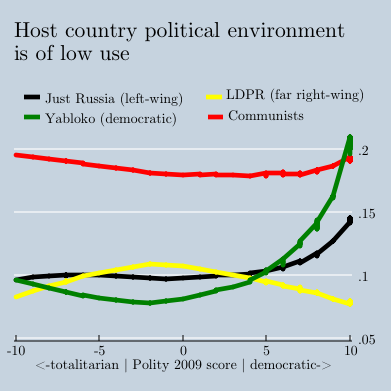

Should per head GDP pass the threshold, voting for democrats increases more than twofold, whereas the Communists, the major opposing force back in Russia, fail to include high income earners in their base. However, to understand the swings of the far-right party LDPR (yellow line), one should focus not on economic but rather on institutional properties of any country where Russian expats vote. Polity IV project assigns a value on the scale from −10 (hereditary monarchy) to +10 (consolidated democracy) to every state:

Voters living in a “freer” country (higher Polity score) are less likely to support far-right, notoriously nationalist political agenda of LDPR. With a caveat of crude generalisations it means that voters living in foreign democratic environment not only endorse democracy itself but also the values that accompany it: tolerance, freedom of movement, anti-xenophobia — and include them in their “political menu”.

Fraud abroad

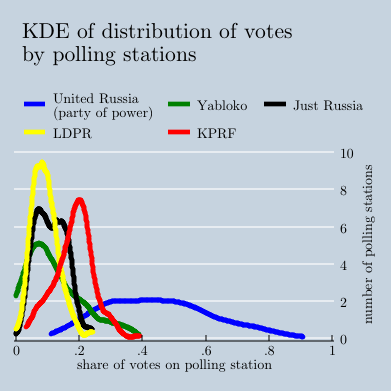

Russian political commentators, statisticians and independent observers agree that fraud accounted for 15-20pp. of votes for the party in power. Unfortunately, the main method of finding the magnitude of fraud is not applicable here as it requires hourly data on voter turnover for every polling station, which is not available for the time being. Nonetheless, we can still analyse “isolated” polling stations:

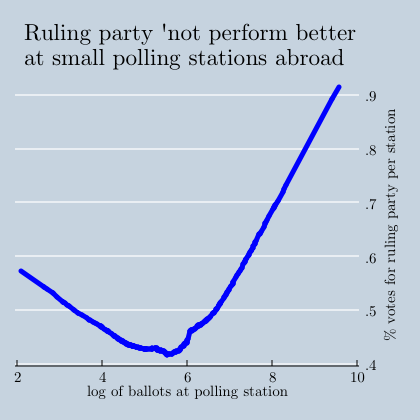

Higher variance and mean for the ruling party (blue line) is the most vivid indication of fraud as it implies either homogeneous voting preferences from country to country, which can hardly be the case, or manipulation with elections outcome. Within Russia the vast majority of fraudulent operations took place on small polling stations: characteristic is the example of a polling station in asylum where the director, approached by a journalist, claimed that not all the voters endorsed the party in power: there were two votes in favour of the Russian czars. But this is not the case for polling stations abroad:

Initial decline may reflect manipulations/involuntary voting but this model has little explanatory power and cannot be used for the purposes of fraud detection.

(This section will be updated when time series data on voter turnover is released)